A pre-recorded video version of this address is available here.

Good morning and welcome again to the annual meeting of the Society of American Archivists. I am honored to be speaking to you this morning as SAA’s 73rd President and would like to express my gratitude for having the opportunity to represent our organization this past year.

Three years ago, our SAA annual meeting theme was about Telling the Story of Archives as part of President Kathleen Roe’s Year of Living Dangerously. Recently the term storytelling just kept popping up everywhere for me. I subscribe to the Brain Pickings newsletter (edited by Maria Popova) which has the literary arts as a focal point. While I often delete the messages due to lack of time, I do save them if a subject catches my eye. And so, while I was reading what I had set aside, the word “Storytelling” appeared three times in conjunction with authors Iris Murdoch, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Susan Sontag. In the next day or so, the SAA Annual Meeting Program came out and I signed up to attend A Finding Aid to My Soul, an open-mic storytelling session tonight. In May, I was interviewed for a blog post on diversity in archives created by Pass It Down, which advertises itself as a digital storytelling company. And finally, just last week, I was standing at the elevator and saw a Wake Forest flyer advertising the MA in Sports Storytelling Program.

Beyond simply telling our own archives stories, though, I realized the term can also be used in how we consider the documentary record. Archives storytelling is, in every way, dependent on recorded evidence and memory. Researchers use the records we collect to make sense of the past, present, and future. Through archives and their use, there is a cycle of storytelling with multiple characters and perspectives, different endings, and even never endings.

As Murdoch observes “we are constantly employing language to make interesting forms out of experience which perhaps originally seemed dull or incoherent.” The making of sense belongs to the genealogists, researchers, scholars, and students who visit us or view our materials online. We can only hope that what we have acquired and collected can provide those interesting forms.

We need to remember that as Sontag points out “To tell a story is to say: this is the important story. It is to reduce the spread and simultaneity of everything to something linear, a path.” This is why we collect about inadequately represented communities, create a documentation strategy, or interview and capture the stories of those who have been left out of the historical record. Wherever archivists focus their attention and effort can expand the number of stories told.

Finally, Le Guin observed that “One of the functions of archives is to give people the words to know their own experience… Storytelling is a tool for knowing who we are and what we want.”

However, how do we tell our story? The story of archivists? Who are we, and what do we want?

So, here is a short tale of what SAA (and when I say SAA, I mean all of us) has been working on over the past year. I’ll focus in particular on Advocacy, Diversity, the SAA Foundation, and Membership. There will be more to come in a forthcoming article in the American Archivist.

Advocacy

One of the primary ways we tell our story—for archivists, users, and the records, is through the practice of advocacy. Nothing could have prepared me for the onslaught of historical record issues for this past year or two, especially at the federal record level. Public records, including local and state records, truly are essential to the functioning of American democracy. In my years as SAA President and Vice President, we have created numerous issue briefs and position statements, signed letters and petitions, and responded to external requests representing crucial national records concerns. The most recent relate to our support of the Presidential Records Act, concern over the illegal removal of Iraqi records from Iraq, and opposing the nomination of Gina Haspel as Director of the CIA (given her destruction of records documenting torture). We spoke about the importance of Net Neutrality, the Use of Private Email by all government officials, the need for Transparency in Public Records, the Value and Importance of the U.S. Census, and Police Mobile Camera Footage as a Public Record. For anyone interested in the labor-intensive and complex process by which these briefs and statements come to pass, please see my Off the Record blog post from July 16.

Why does SAA dedicate its time to advocacy and why is this important for us? Archivists play a special role in the preservation of the historical record and in many cases the preservation and access of these records are dependent on our local, state, and federal governments. Awareness building also allows us to share who we are with the public and why records are integral to their lives. Through these efforts we do our best to ensure that archival sources protect the rights of individuals and organizations, assure the continued accountability of governments and institutions based on evidence, and safeguard access to historical information and cultural heritage.

Diversity

Fostering diversity and inclusion within the profession continues to be a high priority for SAA. Fundraising for the MOSAIC Scholarship and the Brenda S. Banks Travel Award continues, and our key partnership with the Association of Research Libraries in the IMLS-funded Mosaic Fellows Program will last 2 and possibly 3 more years. I am also pleased to again announce that Council endorsed the Native American Protocols earlier this week.

The Task Force on Accessibility is updating our 2010 Best Practices for Working with Archives Employees and Users with Physical Disabilities and is expanding them to include neuro-disabilities, temporary disabilities, and others that may be in scope. A draft was shared earlier this week with Council, and member review will take place shortly.

Our Tragedy Response Initiative Task Force was proposed by our Diverse Sexuality and Gender Section, who were motivated by the Pulse Night Club tragedy as well as far too many other incidents in the past few years. The TF will provide guidance regarding policies, procedures, and best practices for acquisition, deaccessioning, preservation, and access of memorial collections. An update was provided in the Off the Record blog post on July 30 and a final report will be submitted by 2020.

Finally, sharing our expertise should be a priority. In my first job at the Alabama Department of Archives and History, I learned to process and describe collections and to grapple with the enormity, complexity and, quite often, the awfulness of American history. As a transplanted Yankee, it didn’t take me long to figure out the reason for the Confederate flag above the Capitol, or why the state holidays list included Confederate Memorial Day and Martin Luther King, Jr./Robert E. Lee Day (still). I understood too well why the street on which I was fortunate to attend the dedication of the Civil Rights Memorial at the Southern Poverty Law Center also hosted a Ku Klux Klan march several years later. This is not isolated to Alabama, or even to one region of our country. The symbols of oppression and our violent past are all around us.

Last fall’s events in Charlottesville point to the need for archivists to use our skills and experience to assist our communities in researching and determining the history of the names, images, and monuments in our midst. The Council’s Diversity and Inclusion Working Group has begun the process of creating a series of Diversity Toolkits available online for archivists and anyone else who needs its resources. The resources currently include materials for facilitating discussions, helping communities in crisis, researching monuments, and how to teach hard history at the K-12 level. A Bibliography for Monuments and Symbols of Oppression is also available on the SAA web site via an Off the Record blog post. The goal is to provide a starting point to learn more about these issues.

All this work is good. But more needs to be done. Diversity and Inclusion is not simply the purview of the Diversity Committee or our Sections or Council but is a responsibility for all of us.

SAA Foundation

Too many archival stories this past year have involved natural disasters–hurricanes, earthquakes, floods, and the terrifying fires on the west coast. Fortunately, the SAA Foundation’s National Disaster Recovery Fund was expanded in 2017 to include eligibility for Mexico and non-US Caribbean Islands and to award up to $5,000 in grant funding. As you can imagine, Hurricane Maria and the Mexican earthquake damaged many archival repositories. To date, the Foundation has awarded nine grants to archivists and repositories in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Mexico. We are grateful to our Latin American & Caribbean Cultural Heritage Archives Section for translating the application materials. We have a growing role to play in the American hemisphere and it is important we take that responsibility seriously.

The Foundation also supported a new travel grants program for 2018 to provide grants of up to $1,000 each for travel to attend the SAA Annual Meeting. We received nearly 80 applications for 10 grants! Sustainable funding for professional development is an obvious problem for archivists and so as I transition to the position of Immediate Past President and remain on the SAA Foundation Board for (at least) one more year, one of my goals will be to explore how we can connect with external foundations and match their available funding and interests with our needs. In the meantime, I am happy to report that SAA Foundation Board recently approved $10,000 in travel grants for Austin 2019.

Membership and Professional Development

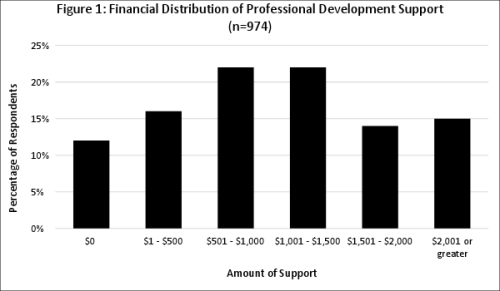

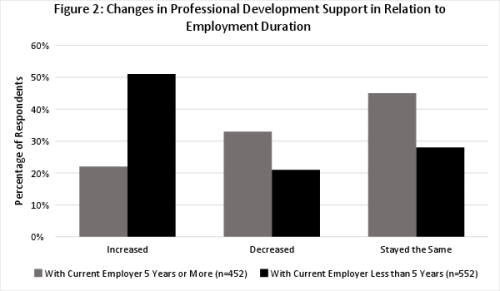

Recently, SAA has undertaken two recent membership surveys, one focused on institutional support for professional development and the other for the needs and interests of mid-career archivists. The results provided key data about what our members need for their success. I mentioned exploring foundation support for professional development, but we also obtained good information about what continuing education archivists would like to see SAA provide—courses on career planning, management, and leadership, among others. Your feedback in these surveys provide a path for SAA to follow over the next several years.

SAA members have recently reviewed the updated Principles of the Annual Meeting, the Code of Ethics, Best Practices for Internships as a Component of a Graduate Archival Program, and Best Practices for Volunteers. Treat these as the opportunities they are for having your voice heard. And never feel hesitant to contact your elected officers and Council.

These are only some of the SAA stories from the past year.

Here are some Recommendations for SAA’s Future.

First and foremost, we need to refocus our energies for Diversity and Inclusion. How can we better document and share the unique diversity projects being undertaken in so many of our repositories? Archivists need to create case studies, essays, and articles and make them available through the SAA website–this can help us ensure our important collection development efforts inspire others to establish new programs. The Diversity Toolkits also need to be finalized and we need all our members to contribute ideas and sources. If everyone in this room submitted a 500-word annotated source, the Toolkits would be a tremendous crowd-based resource for all. There will be a call after the annual meeting, so please plan to send in your suggestions.

Second, we need more information about the makeup of our profession so that SAA can work to meet the many needs of its members. In his 2016 President’s Address, Dennis Meissner called for the creation of a Task Force on Research/Data and Evaluation. The Task Force, created last fall, presented some preliminary findings at the May Council meeting. What questions would I like to see answered about us?

- What is the current breakdown in percentage of degrees held by archivists? Thirty years ago, the predominant source of archives degrees was history programs. In A*CENSUS (2004), the breakdown was 39.4% for the MLS/MLIS vs 46.3% for the MA/MS/MFA. It now appears that most archivists entering the field are coming from library school programs—but it would be good to have those numbers confirmed. However, there are still many, many people working as archivists who chose another path to this profession. How can archivists coming from different backgrounds—and, in some cases, philosophies—communicate and collaborate most effectively? How can our continuing education programs assist in fostering community among such a disparate group?

- How can we better collaborate with the graduate programs which funnel students into the profession? I have heard comments about the number of graduates and the perception they are overwhelming a small job market. SAA has done many evaluations and reports which indicate we simply cannot afford the cost of an official accreditation process. So, it may be time to think creatively about what SAA CAN do.

- We can collect better documentation of all archives graduate programs, no matter the discipline, and increase the understanding of their strengths

- We could collaborate with archival educators and host an annual forum as an invited opportunity for all archives program representatives, educators, and practicing archivists to meet and discuss issues?

- We can foster forums for the various degree programs to discuss curriculum and other issues impacting archives students

- We can explore collaborative assessment projects for programs and highlight student projects from a variety of programs?

- We can collect better documentation of all archives graduate programs, no matter the discipline, and increase the understanding of their strengths

- As a profession, we also need more information about archivists’ salaries, organized by location, type of degree, type of repository, and geographic location. These data would give us important information that would enhance our programming and advocacy efforts. Increasingly, job ads with no salaries are the norm—how can we encourage more transparency for the profession? The National Council on Public History and the American Association for State and Local History recently introduced policies that any job ads shared on their site must have salaries posted. And as with the American Library Association, it would be good for SAA to provide an average salary by state in order to strengthen archivists’ negotiating power.

- Knowing more about the various subsets of SAA membership would also be helpful, as we try to collect more valid and useful data. As I mentioned previously, what has happened to the Mosaic Scholarship participants, Mosaic Fellows, and Harold J. Pinkett Scholars? Are they still in the profession or have they moved to other careers? Why? How can we truly assess and improve our recruiting and retention efforts to expand the diversity of the profession? How effective is our mentoring program? Does our partnering structure work? How can we improve this experience? It is time to explore the ways we can truly examine our hiring and organizational practices.

- It is apparent that the archives profession has many economic issues. These range from how graduates find the programs they attend, the lack of underrepresented communities participating as archivists, the increasing number of students, the limited number of permanent positions, and the overwhelming prevalence of Part-Time and Temporary positions, among others. SAA members recently reviewed the Best Practices for Internships and Volunteers, with many good ideas for revisions. However, in addition to these Best Practices I would suggest we proactively develop solutions for institutions to consider.Some possible ideas:

- Investigate grant possibilities for the support, either profession-wide, or a consortium of institutions, much like our MOSAIC program to provide financial support

- Fundraising in your home institution to create endowments or expendable accounts to support interns, and SAA-developed guidelines on how to make that happen.

- Provide best practices to guide archivists communicating with their local graduate archives programs (who require internships as part of their degree process) to discuss these concerns further and develop ways to either provide support for interns, tuition remission, or provide the credit hours without cost to the student.

Given that the Task Force will most likely recommend the creation of an SAA Committee dedicated to Research, I would therefore propose the consideration of a subcommittee answering to the larger group. This subcommittee would be specifically dedicated to economic equity and collect data about employment matters, including benefits, internships, salaries, how and when graduates enter entry-level positions, promotions, retirement, and broader work topics such as developing apprenticeship programs and how to make our labor visible.

Until we have the data and the ability to thoroughly analyze the results, it is difficult for SAA to respond in a substantive manner.

It will always be difficult for a large/complex organization to move nimbly and be flexible, given competing priorities and SAA’s commitment to building consensus. Does SAA always get it right? Of course not.

However, I would argue that SAA succeeds more often than it fails. And I would like to believe that we are an organization that learns from its mistakes to do things better the next time.

Much like democracy, SAA is us, after all.

Challenges for the Archives Profession

While SAA faces significant tests, the broader archives profession also faces challenges. Sometimes these intersect and overlap, but not always. By joining SAA, you have already chosen a leadership position for the profession, and it is important to 1) be knowledgeable about organizations and affiliated professions other than your own and 2) consider how decision-making and discussions can also affect non-SAA members.

- The Value of the Public Record

Over the past three decades, there have been increasing pressures on the very concept of public records, something so key to the functioning of our American democracy. Secrecy and efforts to hide corruption and wrongdoing and “fake news” have been present in our political life dating back to the earliest days of the Republic. As we now live in a digital world, many of our basic beliefs about what can be controlled in the creation or alteration of a record, its authenticity and very meaning are called into question. Preservation and access to the public record, whether you are a government records archivist or not, should be a concern to you as a citizen.

The political spoils of our election system do have consequences for the historical record and have a direct impact on the efficacy of the archival enterprise. Current challenges for government archives sustainability include the overall shrinkage of governments and budget cuts for archives; the political appointments of individuals without archives experience or backgrounds; archives being subsumed by government bureaucracy and overwhelmed by unfunded mandates; and officials not understanding the role or importance of electronic records and digital preservation.

Citizens still have ways to challenge and question records restriction or destruction and protect open access, including FOIA requests, Sunshine laws, and calls for public comment on appraisal decisions. Just two weeks ago, CREW (Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington) have brought Federal Records Act (FRA) lawsuits against the EPA, filed a FOIA request with the State Department, and after filing a complaint with NARA, an investigation is underway to determine if the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) violated the law by deleting records of immigrant families split at the border.

I would ask of you to serve as archives experts and responsible citizens to closely monitor your local archives, state archives and SHRABS, and NARA. Be an advocate and stay informed. Write letters to the local newspapers and talk with your legislators and representatives about the importance of archives. There are advocacy publications and affordable webinars forthcoming from SAA—use them. SAA and individual archivists have an important role to play as consistent and constant advocates.

- International Human Rights

I represented SAA at the International Council on Archives in Mexico City last fall and I came to some conclusions about the importance of SAA’s international activities. We have a major role to play in the American hemisphere and world, not only as a role model, but also sharing resources such as disaster funding, copyright discussions, and developing collaborative projects which can impact archivists in multiple countries. Given our meeting location in Austin next year, I would very much like to see a concerted effort to invite archivists from throughout the American hemisphere, especially Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central and Southern America to join us and discuss both the questions and possibilities.

The documentation of human rights was also discussed. Past SAA President and former Interim Archivist of the United States Trudy Petersen reported on her work with Swisspeace, an effort (in collaboration with ICA) to preserve records in digital format in different geographic locations for protection purposes. They recently shared the draft Guiding Principles for Safe Havens for Archives at Risk for comment from the archives community. Amnesty International is also announcing a project for the preservation of digital records. According to their press release, “the new archive will accelerate investigations into human rights violations and protect digital records of significant historical importance to the global movement.” It is important we support this work and recognize that both activists and archivists play a role in ensuring the preservation and access to these records.

- Allied Memory Organizations and Professions

The various communities comprising digital humanities, digital libraries, history, library, museum, and public history fields that overlap with the archives profession continue to expand and splinter. There is a distinct need to map our associated collection and memory professions and how our grants, projects, and research activities impact all of us.

Later today, we will be meeting with representatives of nearly 20 organizations, including the American Association for State and Local History, the Association for Moving Image Archivists, the Coalition for Networked Information, the Digital Library Federation, and RBMS, among others. We plan to discuss how we can more effectively collaborate and share information about data gathering, advocacy strategies, research methodologies, and user infrastructure, when we remain so incredibly siloed.

- Leadership and Service

I want to conclude this presentation with some brief points about your own leadership practice as I believe this is where SAA truly has so much to offer to each of you. Both SAA and the archives profession need you. It needs every one of you—your energy, your willingness to work hard, your perspective. Keep these things in mind as you write your own story.

Be strategic and mindful about your archives career and service. Dedicate yourself to what you truly care about and are willing to spend the time on.

Leaders are made, not born. Consider every experience you have as an important step on your path and as a part of your individual story.

Believe in yourself and share yourself with others. Smile and say hello to someone at this meeting you don’t know. Share a story from your archives. Find a mentor. Be a mentor. When a colleague calls on you for advice, answer.

Finally, I would also advise the following given how emotionally taxing our work can be at times.

Remember why you do what you do. Take time for reflection and introspection.

Take comfort in the friendship and support of your archives friends and colleagues.

Appreciate and feel the gratitude of your donors, no matter if they are individuals, offices, or agencies.

Remember the integral role you play in creating the historical record. Be creative and strategic on how you accomplish your vocation.

And here’s my final thought. While archivists are about records, what we really are about is people. The people who created and saved the records, present, past, and future and the people who want to use them to construct new narratives. Our mission is how can we best serve as thoughtful and dedicated intermediaries to ensure their stories and lives are not forgotten.

Thank you for sharing this time with me today.